Modelling composition with Semigroups

A semigroup is a recipe to combine two, or more, values.

A semigroup is an algebra, which is generally defined as a specific combination of:

- one or more sets

- one or more operations on those sets

- zero or more laws on the previous operations

Algebras are how mathematicians try to capture an idea in its purest form, eliminating everything that is superfluous.

When an algebra is modified the only allowed operations are those defined by the algebra itself according to its own laws

Algebras can be thought of as an abstraction of interfaces:

When an interface is modified the only allowed operations are those defined by the interface itself according to its own laws

Before getting into semigroups, let's see first an example of an algebra, a magma.

Definition of a Magma

A Magma is a very simple algebra:

- a set or type (A)

- a

concatoperation - no laws to obey

Note: in most cases the terms set and type can be used interchangeably.

We can use a TypeScript interface to model a Magma.

interface Magma<A> {

readonly concat: (first: A, second: A) => A

}

Thus, we have have the ingredients for an algebra:

- a set

A - an operation on the set

A,concat. This operation is said to be closed on the setAwhich means that whichever elementsAwe apply the operation on the result will still be an element ofA. Since the result is still anA, it can be used again as an input forconcatand the operation can be repeated how many times we want. In other wordsconcatis acombinatorfor the typeA.

Let's implement a concrete instance of Magma<A> with A being the number type.

import { Magma } from 'fp-ts/Magma'

const MagmaSub: Magma<number> = {

concat: (first, second) => first - second

}

// helper

const getPipeableConcat = <A>(M: Magma<A>) => (second: A) => (first: A): A =>

M.concat(first, second)

const concat = getPipeableConcat(MagmaSub)

// usage example

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/function'

pipe(10, concat(2), concat(3), concat(1), concat(2), console.log)

// => 2

Quiz. The fact that concat is a closed operation isn't a trivial detail. If A is the set of natural numbers (defined as positive integers) instead of the JavaScript number type (a set of positive and negative floats), could we define a Magma<Natural> with concat implemented like in MagmaSub? Can you think of any other concat operation on natural numbers for which the closure property isn't valid?

See the answer here

Definition. Given A a non empty set and * a binary operation closed on (or internal to) A, then the pair (A, *) is called a magma.

Magmas do not obey any law, they only have the closure requirement. Let's see an algebra that do requires another law: semigroups.

Definition of a Semigroup

Given a

Magmaif theconcatoperation is associative then it's a semigroup.

The term "associative" means that the equation:

(x * y) * z = x * (y * z)

// or

concat(concat(a, b), c) = concat(a, concat(b, c))

holds for any x, y, z in A.

In layman terms associativity tells us that we do not have to worry about parentheses in expressions and that we can simply write x * y * z (there's no ambiguity).

Example

String concatenation benefits from associativity.

("a" + "b") + "c" = "a" + ("b" + "c") = "abc"

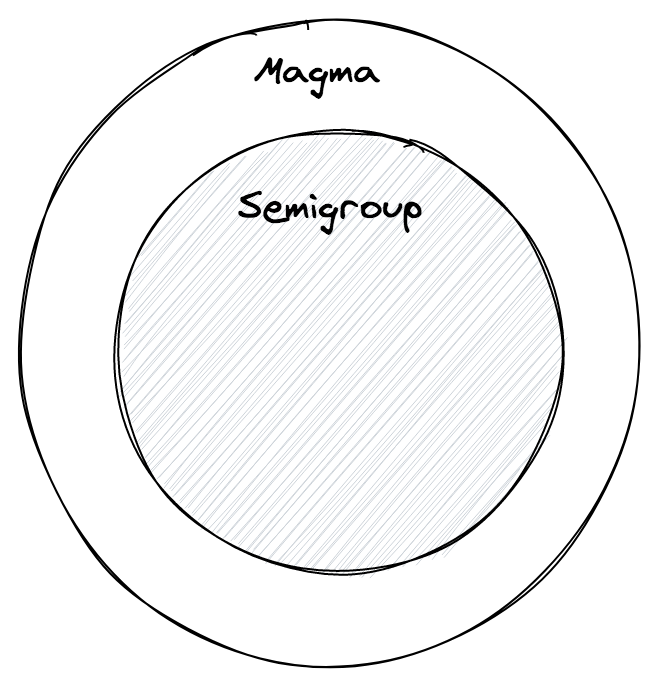

Every semigroup is a magma, but not every magma is a semigroup.

Example

The previous MagmaSub is not a semigroup because its concat operation is not associative.

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/function'

import { Magma } from 'fp-ts/Magma'

const MagmaSub: Magma<number> = {

concat: (first, second) => first - second

}

pipe(MagmaSub.concat(MagmaSub.concat(1, 2), 3), console.log) // => -4

pipe(MagmaSub.concat(1, MagmaSub.concat(2, 3)), console.log) // => 2

Semigroups capture the essence of parallelizable operations

If we know that there is such an operation that follows the associativity law, we can further split a computation into two sub computations, each of them could be further split into sub computations.

a * b * c * d * e * f * g * h = ((a * b) * (c * d)) * ((e * f) * (g * h))

Sub computations can be run in parallel mode.

As for Magma, Semigroups are implemented through a TypeScript interface:

// fp-ts/lib/Semigroup.ts

interface Semigroup<A> extends Magma<A> {}

The following law has to hold true:

- Associativity: If

Sis a semigroup the following has to hold true:

S.concat(S.concat(x, y), z) = S.concat(x, S.concat(y, z))

for every x, y, z of type A

Note. Sadly it is not possible to encode this law using TypeScript's type system.

Let's implement a semigroup for some ReadonlyArray<string>:

import * as Se from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

const Semigroup: Se.Semigroup<ReadonlyArray<string>> = {

concat: (first, second) => first.concat(second)

}

The name concat makes sense for arrays (as we'll see later) but, depending on the context and the type A on whom we're implementing an instance, the concat semigroup operation may have different interpretations and meanings:

- "concatenation"

- "combination"

- "merging"

- "fusion"

- "selection"

- "sum"

- "substitution"

and many others.

Example

This is how to implement the semigroup (number, +) where + is the usual addition of numbers:

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

/** number `Semigroup` under addition */

const SemigroupSum: Semigroup<number> = {

concat: (first, second) => first + second

}

Quiz. Can the concat combinator defined in the demo 01_retry.ts be used to define a Semigroup instance for the RetryPolicy type?

See the answer here

This is the implementation for the semigroup (number, *) where * is the usual number multiplication:

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

/** number `Semigroup` under multiplication */

const SemigroupProduct: Semigroup<number> = {

concat: (first, second) => first * second

}

Note It is a common mistake to think about the semigroup of numbers, but for the same type A it is possible to define more instances of Semigroup<A>. We've seen how for number we can define a semigroup under addition and multiplication. It is also possible to have Semigroups that share the same operation but differ in types. SemigroupSum could've been implemented on natural numbers instead of unsigned floats like number.

Another example, with the string type:

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

const SemigroupString: Semigroup<string> = {

concat: (first, second) => first + second

}

Another two examples, this time with the boolean type:

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

const SemigroupAll: Semigroup<boolean> = {

concat: (first, second) => first && second

}

const SemigroupAny: Semigroup<boolean> = {

concat: (first, second) => first || second

}

The concatAll function

By definition concat combines merely two elements of A every time. Is it possible to combine any number of them?

The concatAll function takes:

- an instance of a semigroup

- an initial value

- an array of elements

import * as S from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

import * as N from 'fp-ts/number'

const sum = S.concatAll(N.SemigroupSum)(2)

console.log(sum([1, 2, 3, 4])) // => 12

const product = S.concatAll(N.SemigroupProduct)(3)

console.log(product([1, 2, 3, 4])) // => 72

Quiz. Why do I need to provide an initial value?

-> See the answer here

Example

Lets provide some applications of concatAll, by reimplementing some popular functions from the JavaScript standard library.

import * as B from 'fp-ts/boolean'

import { concatAll } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

import * as S from 'fp-ts/struct'

const every = <A>(predicate: (a: A) => boolean) => (

as: ReadonlyArray<A>

): boolean => concatAll(B.SemigroupAll)(true)(as.map(predicate))

const some = <A>(predicate: (a: A) => boolean) => (

as: ReadonlyArray<A>

): boolean => concatAll(B.SemigroupAny)(false)(as.map(predicate))

const assign: (as: ReadonlyArray<object>) => object = concatAll(

S.getAssignSemigroup<object>()

)({})

Quiz. Is the following semigroup instance lawful (does it respect semigroup laws)?

See the answer here

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

/** Always return the first argument */

const first = <A>(): Semigroup<A> => ({

concat: (first, _second) => first

})

Quiz. Is the following semigroup instance lawful?

See the answer here

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

/** Always return the second argument */

const last = <A>(): Semigroup<A> => ({

concat: (_first, second) => second

})

The dual semigroup

Given a semigroup instance, it is possible to obtain a new semigroup instance by simply swapping the order in which the operands are combined:

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/function'

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

import * as S from 'fp-ts/string'

// This is a Semigroup combinator

const reverse = <A>(S: Semigroup<A>): Semigroup<A> => ({

concat: (first, second) => S.concat(second, first)

})

pipe(S.Semigroup.concat('a', 'b'), console.log) // => 'ab'

pipe(reverse(S.Semigroup).concat('a', 'b'), console.log) // => 'ba'

Quiz. This combinator makes sense because, generally speaking, the concat operation is not commutative, can you find an example where concat is commutative and one where it isn't?

See the answer here

Semigroup product

Let's try defining a semigroup instance for more complex types:

import * as N from 'fp-ts/number'

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

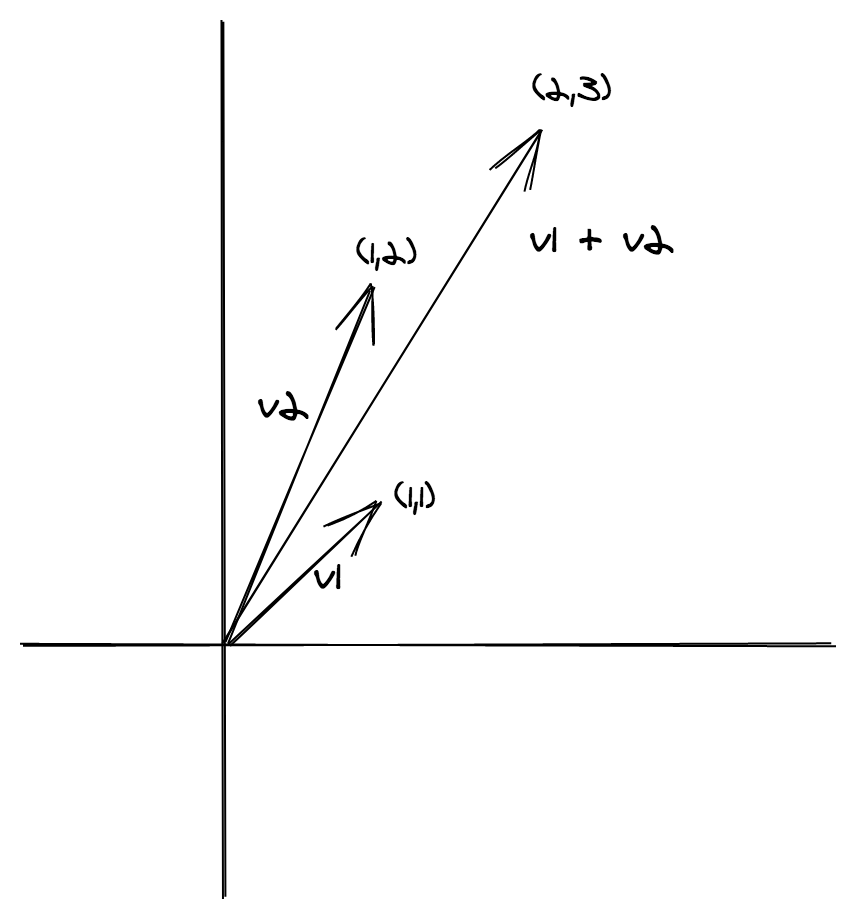

// models a vector starting at the origin

type Vector = {

readonly x: number

readonly y: number

}

// models a sum of two vectors

const SemigroupVector: Semigroup<Vector> = {

concat: (first, second) => ({

x: N.SemigroupSum.concat(first.x, second.x),

y: N.SemigroupSum.concat(first.y, second.y)

})

}

Example

const v1: Vector = { x: 1, y: 1 }

const v2: Vector = { x: 1, y: 2 }

console.log(SemigroupVector.concat(v1, v2)) // => { x: 2, y: 3 }

Too much boilerplate? The good news is that the mathematical theory behind semigroups tells us we can implement a semigroup instance for a struct like Vector if we can implement a semigroup instance for each of its fields.

Conveniently the fp-ts/Semigroup module exports a struct combinator:

import { struct } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

// models the sum of two vectors

const SemigroupVector: Semigroup<Vector> = struct({

x: N.SemigroupSum,

y: N.SemigroupSum

})

Note. There is a combinator similar to struct that works with tuples: tuple

import * as N from 'fp-ts/number'

import { Semigroup, tuple } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

// models a vector starting from origin

type Vector = readonly [number, number]

// models the sum of two vectors

const SemigroupVector: Semigroup<Vector> = tuple(N.SemigroupSum, N.SemigroupSum)

const v1: Vector = [1, 1]

const v2: Vector = [1, 2]

console.log(SemigroupVector.concat(v1, v2)) // => [2, 3]

Quiz. Is it true that given any Semigroup<A> and having chosen any middle of A, if I insert it between the two concat parameters the result is still a semigroup?

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/function'

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

import * as S from 'fp-ts/string'

export const intercalate = <A>(middle: A) => (

S: Semigroup<A>

): Semigroup<A> => ({

concat: (first, second) => S.concat(S.concat(first, middle), second)

})

const SemigroupIntercalate = pipe(S.Semigroup, intercalate('|'))

pipe(

SemigroupIntercalate.concat('a', SemigroupIntercalate.concat('b', 'c')),

console.log

) // => 'a|b|c'

Finding a Semigroup instance for any type

The associativity property is a very strong requirement, what happens if, given a specific type A we can't find an associative operation on A?

Suppose we have a type User defined as:

type User = {

readonly id: number

readonly name: string

}

and that inside my database we have multiple copies of the same User (e.g. they could be historical entries of its modifications).

// internal APIs

declare const getCurrent: (id: number) => User

declare const getHistory: (id: number) => ReadonlyArray<User>

and that we need to implement a public API

export declare const getUser: (id: number) => User

which takes into account all of its copies depending on some criteria. The criteria should be to return the most recent copy, or the oldest one, or the current one, etc..

Naturally we can define a specific API for each of these criterias:

export declare const getMostRecentUser: (id: number) => User

export declare const getLeastRecentUser: (id: number) => User

export declare const getCurrentUser: (id: number) => User

// etc...

Thus, to return a value of type User I need to consider all the copies and make a merge (or selection) of them, meaning I can model the criteria problem with a Semigroup<User>.

That being said, it is not really clear right now what it means to "merge two Users" nor if this merge operation is associative.

You can always define a Semigroup instance for any given type A by defining a semigroup instance not for A itself but for NonEmptyArray<A> called the free semigroup of A:

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

// represents a non-empty array, meaning an array that has at least one element A

type ReadonlyNonEmptyArray<A> = ReadonlyArray<A> & {

readonly 0: A

}

// the concatenation of two NonEmptyArrays is still a NonEmptyArray

const getSemigroup = <A>(): Semigroup<ReadonlyNonEmptyArray<A>> => ({

concat: (first, second) => [first[0], ...first.slice(1), ...second]

})

and then we can map the elements of A to "singletons" of ReadonlyNonEmptyArray<A>, meaning arrays with only one element.

// insert an element into a non empty array

const of = <A>(a: A): ReadonlyNonEmptyArray<A> => [a]

Let's apply this technique to the User type:

import {

getSemigroup,

of,

ReadonlyNonEmptyArray

} from 'fp-ts/ReadonlyNonEmptyArray'

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

type User = {

readonly id: number

readonly name: string

}

// this semigroup is not for the `User` type but for `ReadonlyNonEmptyArray<User>`

const S: Semigroup<ReadonlyNonEmptyArray<User>> = getSemigroup<User>()

declare const user1: User

declare const user2: User

declare const user3: User

// const merge: ReadonlyNonEmptyArray<User>

const merge = S.concat(S.concat(of(user1), of(user2)), of(user3))

// I can get the same result by "packing" the users manually into an array

const merge2: ReadonlyNonEmptyArray<User> = [user1, user2, user3]

Thus, the free semigroup of A is merely another semigroup in which the elements are all possible, non empty, finite sequences of A.

The free semigroup of A can be seen as a lazy way to concatenate elements of type A while preserving their data content.

The merge value, containing [user1, user2, user3], tells us which are the elements to concatenate and in which order they are.

Now I have three possible options to design the getUser API:

- I can define

Semigroup<User>and I want to get straight intomergeing.

declare const SemigroupUser: Semigroup<User>

export const getUser = (id: number): User => {

const current = getCurrent(id)

const history = getHistory(id)

return concatAll(SemigroupUser)(current)(history)

}

- I can't define

Semigroup<User>or I want to leave the merging strategy open to implementation, thus I'll ask it to the API consumer:

export const getUser = (SemigroupUser: Semigroup<User>) => (

id: number

): User => {

const current = getCurrent(id)

const history = getHistory(id)

// merge immediately

return concatAll(SemigroupUser)(current)(history)

}

- I can't define

Semigroup<User>nor I want to require it.

In this case the free semigroup of User can come to the rescue:

export const getUser = (id: number): ReadonlyNonEmptyArray<User> => {

const current = getCurrent(id)

const history = getHistory(id)

// I DO NOT proceed with merging and return the free semigroup of User

return [current, ...history]

}

It should be noted that, even when I do have a Semigroup<A> instance, using a free semigroup might be still convenient for the following reasons:

- avoids executing possibly expensive and pointless computations

- avoids passing around the semigroup instance

- allows the API consumer to decide which is the correct merging strategy (by using

concatAll).

Order-derivable Semigroups

Given that number is a total order (meaning that whichever x and y we choose, one of those two conditions has to hold true: x <= y or y <= x) we can define another two Semigroup<number> instances using the min or max operations.

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

const SemigroupMin: Semigroup<number> = {

concat: (first, second) => Math.min(first, second)

}

const SemigroupMax: Semigroup<number> = {

concat: (first, second) => Math.max(first, second)

}

Quiz. Why is it so important that number is a total order?

It would be very useful to define such semigroups (SemigroupMin and SemigroupMax) for different types than number.

Is it possible to capture the notion of being totally ordered for other types?

To speak about ordering we first need to capture the notion of equality.